Introduction

Laboratory test results are the cornerstone of modern clinical decision-making, forming the basis for diagnosis, treatment planning, and patient monitoring. However, the reliability of these results hinges on multiple factors, including the integrity of the specimens submitted for analysis. Among these factors, pre-analytical errors—errors that occur before the actual testing process—are recognized as a leading cause of inaccurate laboratory results, potentially leading to significant clinical consequences.

In 2000, the Institute of Medicine reported that medical errors, including those involving laboratory diagnostics, contribute to an estimated 44,000–98,000 preventable deaths annually in the United States. Errors due to inaccurate laboratory testing are particularly impactful, as they can propagate misdiagnoses, inappropriate treatments, or delays in necessary care. This emphasizes the critical need for laboratories to address pre-analytical issues comprehensively, especially those arising from endogenous interfering substances like hemolysis, lipemia, and high bilirubin levels (icterus).

The Prevalence of Endogenous Interfering Substances

Endogenous interfering substances refer to naturally occurring elements in the blood—such as red cell debris, lipoproteins, or bilirubin—that disrupt analytical processes. These substances are a leading cause of analytical errors in laboratory testing and are often overlooked due to their subtle effects on test results. A study highlighted that 9.7% of outpatient samples and 16.5% of emergency department samples contained one or more interfering substances, with 12.4% of emergency samples exhibiting hemolysis. Such findings underscore the ubiquity of these substances in clinical specimens and their significant role in generating erroneous results.

Mechanisms of Analytical Interference

The mechanisms by which hemolysis, lipemia, and icterus interfere with laboratory testing are multifaceted:

- Spectral Interference: Many endogenous substances absorb or scatter light in the same spectral ranges used in photometric assays, leading to inaccurate analyte measurements.

- Chemical Interference: Substances such as hemoglobin and bilirubin can participate in chemical reactions with assay reagents, altering the expected results.

- Dilution Effects: The release of intracellular contents from lysed cells or the displacement of plasma water by lipids can dilute or concentrate analytes, distorting their measured values.

Importance of Addressing Pre-Analytical Errors

Despite the development of advanced technologies and protocols, pre-analytical errors remain a persistent challenge. These errors are often undetected or underestimated in routine laboratory operations. For example:

- Hemolysis: Mismanagement during blood collection or processing can cause erythrocyte rupture, leading to the release of intracellular contents that distort test outcomes.

- Lipemia: Elevated lipids in the blood scatter light in spectrophotometric assays, masking or altering analyte concentrations.

- Icterus: High bilirubin levels interfere with assays by chemically reacting with reagents or spectrophotometrically absorbing light in overlapping wavelengths.

Failure to address these interferences not only compromises the accuracy of individual test results but also undermines the broader reliability of laboratory data in clinical practice.

Addressing the Challenges

The detection and mitigation of endogenous interferences require a multi-pronged approach:

- Visual Inspection: Manual assessment of sample appearance can identify severe hemolysis, lipemia, or icterus, but subtle interferences may remain undetected.

- Automated Detection: Modern analyzers are increasingly equipped with algorithms to flag and quantify interfering substances, enabling laboratories to adjust or reject affected results.

- Standardized Handling Procedures: Proper specimen collection, transport, and storage protocols are essential to minimizing pre-analytical errors.

Pre-analytical errors stemming from endogenous interfering substances represent a significant challenge in clinical laboratory testing. By understanding the prevalence, mechanisms, and impact of these interferences, laboratories can implement targeted strategies to reduce errors and improve patient outcomes. In subsequent sections, this article will delve deeper into the specific effects of hemolysis, lipemia, and icterus, offering evidence-based recommendations for mitigating their impact.

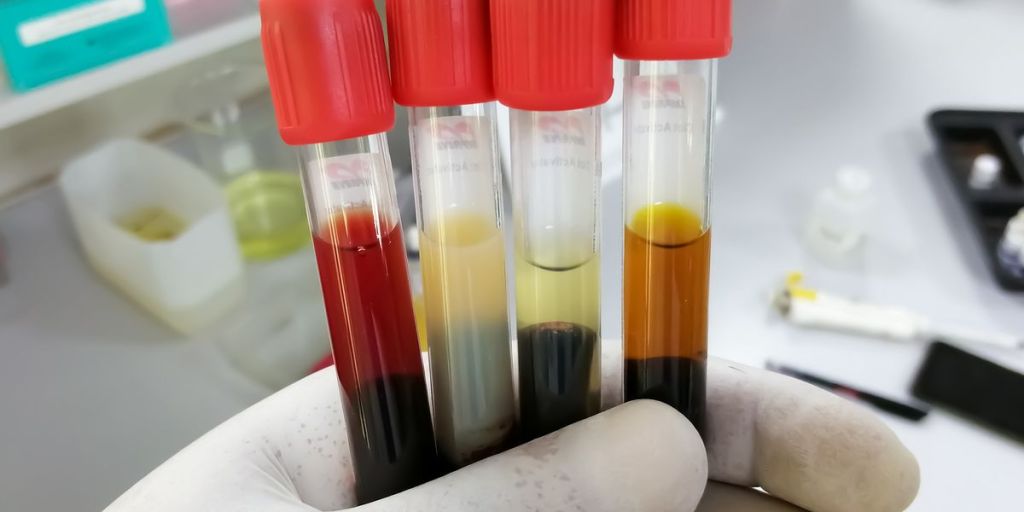

Image courtesy of Clinical Lab Products. Source: https://www.clinicallab.com/hemolysis-icterus-and-lipemia-interference-new-approaches-to-old-foes-26664.”

Hemolysis: Mechanisms and Impacts

Definition and Mechanism

Hemolysis refers to the rupture of erythrocytes, leading to the release of intracellular contents—such as hemoglobin, potassium, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and aspartate aminotransferase (AST)—into the surrounding serum or plasma. Hemolysis can occur in vivo (within the patient’s circulatory system) or in vitro (during or after sample collection). While in vivo hemolysis is associated with pathological conditions, in vitro hemolysis is predominantly caused by pre-analytical errors during specimen collection, transport, or processing.

Key Mechanisms of Hemolysis:

- In Vivo Hemolysis:

- Caused by underlying medical conditions, such as autoimmune hemolytic anemia, hereditary spherocytosis, or infections (e.g., malaria, sepsis).

- Results in the release of intracellular components into the bloodstream, affecting systemic homeostasis.

- In Vitro Hemolysis:

- Arises from mechanical stress during phlebotomy (e.g., excessive suction force, improper needle size, or vigorous mixing).

- Sample mishandling during transport or storage, such as delays in processing or exposure to extreme temperatures, can exacerbate hemolysis.

Prevalence:

Hemolysis is the most common source of pre-analytical errors, with studies reporting its occurrence in 9.7% of outpatient samples and 12.4% of emergency department samples. The prevalence is significantly higher in critical care settings, such as neonatal and pediatric wards, due to increased sample fragility and handling challenges.

Analytical Impacts of Hemolysis

Hemolysis introduces endogenous interferents, primarily hemoglobin and intracellular electrolytes, which can alter analytical measurements in the following ways:

- Spectral Interference:

- Hemoglobin absorbs light at wavelengths commonly used in photometric assays, particularly between 340–500 nm and 540–580 nm. This spectral overlap distorts analyte readings, resulting in spurious increases or decreases in test values.

- Examples:

- False elevations in bilirubin when measured by spectrophotometric methods.

- Interference in enzyme activity assays reliant on light absorbance.

- Chemical Interference:

- Intracellular potassium, LDH, and AST released during hemolysis can artificially elevate these analyte levels, mimicking pathological conditions such as hyperkalemia or liver injury.

- Hemoglobin can participate in oxidation-reduction reactions, interfering with assays reliant on such mechanisms (e.g., glucose or cholesterol measurements).

- Dilution Effect:

- The release of intracellular fluid dilutes plasma components, leading to falsely low results for analytes such as sodium, glucose, and chloride.

- Specific Example of Hemolysis-Induced Bias:

- At a hemoglobin concentration of 300 mg/dL, glucose levels may be underestimated by up to 10%. Similarly, the presence of 100 mg/dL of hemoglobin may falsely elevate potassium concentrations.

Clinical Case Studies

Paroxysmal Nocturnal Hemoglobinuria (PNH):

- A 58-year-old female presented with elevated LDH, potassium, and hemoglobin levels in plasma due to intravascular hemolysis.

- The findings were confirmed as in vivo hemolysis using serial sampling and differential assessment of plasma and serum.

In Vitro Hemolysis:

- A sample collected using a narrow-bore needle exhibited increased potassium and LDH, accompanied by low glucose. This was attributed to improper handling and delayed sample processing, leading to hemolysis during clot formation.

Mitigation Strategies for Hemolysis

- Specimen Collection:

- Use properly sized needles (e.g., ≥21 gauge) to minimize mechanical stress on erythrocytes.

- Avoid vigorous mixing of samples and ensure correct filling of collection tubes to prevent air bubbles and clotting-related hemolysis.

- Collect blood into anticoagulant-containing tubes (e.g., heparin) to reduce the risk of clot-induced hemolysis during processing.

- Specimen Transport and Processing:

- Minimize transport delays by promptly delivering specimens to the laboratory for analysis.

- Maintain appropriate temperature conditions to prevent thermal stress.

- Use standardized centrifugation protocols to avoid re-centrifugation errors or excessive speed.

- Automated Detection:

- Many modern analyzers are equipped with hemoglobin quantification algorithms to detect hemolysis and flag affected samples for further review.

- Laboratories can use correction factors to adjust for analytes like potassium or glucose in hemolyzed specimens, though this approach is limited by individual variability in erythrocyte fragility and analyte concentrations.

- Differentiating In Vivo and In Vitro Hemolysis:

- Collect both serum and plasma samples for comparative analysis of potassium and LDH levels.

- Measure additional markers such as haptoglobin, hemoglobin, and reticulocyte counts to confirm in vivo hemolysis.

Hemolysis, particularly in vitro, remains a leading cause of pre-analytical errors in laboratory testing. By understanding its mechanisms and implementing targeted mitigation strategies, laboratories can reduce its occurrence and impact, ensuring the accuracy and reliability of diagnostic results. Advanced automation and quality control systems offer valuable tools for early detection and correction, while strict adherence to specimen handling protocols can prevent hemolysis at its source. Continued efforts to address hemolysis are vital for improving laboratory medicine and minimizing its impact on patient care.

Lipemia: Mechanisms and Analytical Challenges

Definition and Mechanism

Lipemia refers to the presence of elevated levels of lipids, particularly triglyceride-rich lipoproteins such as chylomicrons and very-low-density lipoproteins (VLDL), in blood samples. These lipids create a turbid or milky appearance in plasma or serum, interfering with analytical measurements, primarily through spectrophotometric disruptions. The severity of lipemia is influenced by patient conditions, dietary intake, or parenteral lipid infusions.

Key Mechanisms of Lipemia:

- Turbidity-Induced Interference:

- Lipoproteins scatter light at wavelengths greater than 600 nm, reducing the accuracy of spectrophotometric assays.

- Volume Displacement:

- Triglycerides displace plasma water, reducing the aqueous phase available for analyte solubility and leading to altered measurements.

- Chemical and Physical Effects:

- Lipids can obstruct immunoassay reactions by interfering with antibody binding or analyte access.

- Analytical methods relying on light transmission or reagent mixing are particularly susceptible to disruption.

Analytical Impacts of Lipemia

- Spectrophotometric Interference:

- Lipoproteins scatter light in photometric assays, producing falsely elevated or reduced analyte values depending on the method used.

- Example: Cholesterol or triglyceride measurements are skewed by excessive light scattering caused by lipoproteins, particularly chylomicrons and VLDL.

- Volume Displacement Effect:

- High lipid content displaces plasma water, leading to artificially low measurements of aqueous-phase analytes such as sodium.

- Example: A sample with severe lipemia may show a falsely low sodium concentration due to reduced plasma water content.

- Matrix Effects in Immunoassays:

- Lipids physically obstruct antibody-analyte interactions, reducing assay sensitivity or specificity.

- Example: Hormone assays such as those for thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) or cortisol may yield erroneous results due to lipid interference.

- Chemical Interactions:

- Certain reagents used in enzymatic assays may interact with lipoproteins, producing unpredictable effects.

- Example: Triglyceride interference may alter amylase or lipase results in enzyme-based diagnostic assays.

Prevalence of Lipemia

Lipemia is commonly observed in patients with metabolic disorders or after high-fat meals. Plasma triglyceride concentrations exceeding 1,000 mg/dL are typically associated with visible turbidity. Notable causes include:

- Metabolic Conditions:

- Diabetes mellitus, pancreatitis, and familial hyperlipidemia.

- Dietary Intake:

- Recent high-fat meals can transiently elevate triglyceride levels.

- Lipid Infusions:

- Patients receiving parenteral nutrition or intravenous lipid emulsions (e.g., Intralipid) may develop lipemia.

Clinical Case Studies

- Hypertriglyceridemia and Lipemia:

- A diabetic patient presented with severe hypertriglyceridemia (>1,500 mg/dL), resulting in falsely decreased amylase activity due to light scattering. Ultracentrifugation to remove lipids corrected the amylase results.

- Parenteral Lipid Infusion:

- A patient on prolonged intravenous lipid therapy exhibited falsely elevated cholesterol and triglyceride levels. The interference was resolved by stopping lipid infusion for 12 hours prior to sample collection.

Mitigation Strategies for Lipemia

- Sample Preparation:

- Ultracentrifugation: Physically removes lipids by spinning samples at high speeds to separate lipid-rich fractions from plasma or serum.

- Chemical Precipitation: Certain reagents can precipitate lipids, allowing for their removal prior to analysis.

- Dilution: Diluting the sample can reduce lipid-induced turbidity, though this may affect low-concentration analytes.

- Fasting Samples:

- Collect samples after a minimum 12-hour fasting period to minimize postprandial triglyceride levels. This is particularly important for lipid panels or assays sensitive to turbidity.

- Automated Detection:

- Many modern analyzers flag lipemic samples based on turbidity thresholds. This enables laboratories to identify and manage affected specimens prior to reporting results.

- Reagent and Method Selection:

- Use reagents and assay methods specifically designed to minimize lipid interference. For example:

- Enzymatic assays that incorporate lipid-clearing agents.

- Spectrophotometric assays with wavelength adjustments to reduce light scattering.

- Use reagents and assay methods specifically designed to minimize lipid interference. For example:

- Avoiding Intralipid Artifacts:

- Intralipid emulsions, commonly used in clinical settings, mimic the effects of natural lipids but do not replicate the full spectrum of lipid interference. Laboratories should validate methods specifically against patient-derived lipemic samples.

Lipemia is a significant source of analytical interference, particularly in spectrophotometric and immunoassay-based methods. By understanding the mechanisms through which lipids disrupt analytical accuracy, laboratories can implement effective strategies to mitigate their impact. These include sample preparation techniques such as ultracentrifugation, fasting protocols, and method optimization. Advanced automation and analyzer capabilities provide additional safeguards, allowing for the detection and correction of lipemia-related biases in laboratory results. Through these measures, laboratories can ensure the reliability of diagnostic tests in the presence of lipemia, ultimately supporting accurate clinical decision-making.

Icterus: Mechanisms and Effects on Testing

Definition and Mechanism

Icterus, commonly referred to as jaundice, is characterized by elevated levels of bilirubin in the blood. This condition often arises due to liver dysfunction, excessive hemolysis, or biliary obstruction. Bilirubin, a byproduct of heme degradation, exists in both unconjugated and conjugated forms, which interfere with laboratory assays primarily through spectrophotometric and chemical mechanisms.

Key Mechanisms of Icterus:

- Spectral Interference:

- Bilirubin absorbs light at wavelengths between 340–500 nm, overlapping with many assay detection ranges.

- Conjugated bilirubin’s absorption shifts in alkaline conditions, further complicating photometric measurements.

- Chemical Reactions:

- Bilirubin chemically reacts with reagents such as hydrogen peroxide or oxidase/peroxidase systems, altering the expected assay outcomes.

- Matrix Effects:

- High bilirubin concentrations can affect the solubility, accessibility, or chemical behavior of analytes, interfering with their detection.

Analytical Impacts of Icterus

- Spectral Interference:

- Bilirubin’s absorbance properties directly interfere with photometric assays that rely on light transmission.

- Example: In enzymatic assays, such as glucose or cholesterol measurements, the high absorbance of bilirubin may result in falsely elevated or decreased values.

- Chemical Interference:

- Bilirubin reacts with oxidizing agents used in some assays, such as those measuring uric acid, triglycerides, or creatinine.

- Example: The Jaffe reaction used for creatinine measurement is prone to interference from bilirubin, leading to underestimation of creatinine levels.

- Matrix Effects in Immunoassays:

- Elevated bilirubin may compete with or block antibodies, reducing the specificity of immunoassays.

- Example: Bilirubin interference can reduce the accuracy of thyroid function tests or drug monitoring assays.

Prevalence of Icterus

Icterus is frequently observed in:

- Hepatic Diseases: Conditions like cirrhosis, hepatitis, and cholestasis.

- Neonatal Jaundice: Resulting from immature liver enzyme systems.

- Hemolytic Anemia: Due to excessive red cell destruction and overproduction of unconjugated bilirubin.

High bilirubin levels (>2 mg/dL) are considered clinically significant, with visible jaundice often occurring at levels >3 mg/dL. Severe cases (>20 mg/dL) can lead to substantial analytical interference.

Clinical Case Studies

- Hepatic Dysfunction and Icterus:

- A patient with elevated bilirubin levels presented with falsely low creatinine values due to interference in the Jaffe reaction. The interference was resolved by using a modified enzymatic assay.

- Neonatal Jaundice:

- A neonate with unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia showed spurious elevations in cholesterol and triglyceride measurements. The use of wavelength-specific blanking techniques minimized the interference.

Mitigation Strategies for Icterus

- Sample Preparation:

- Apply blanking methods in spectrophotometric assays to correct for bilirubin’s absorbance properties.

- Use reagents that neutralize bilirubin interference (e.g., hydrogen peroxide scavengers).

- Automated Detection:

- Modern analyzers can detect and flag samples with high bilirubin concentrations, enabling laboratories to adjust or correct results.

- Alternative Methods:

- Enzymatic assays specifically designed to reduce bilirubin sensitivity can minimize chemical interference.

- Perform visual inspections of samples for severe icterus, which often correlates with high bilirubin levels.

- Reporting with Comments:

- Laboratories should report results with caveats indicating potential interference from icterus, especially when bilirubin levels exceed predefined thresholds.

Icterus is a significant source of analytical interference in clinical laboratories, particularly in assays relying on photometric and enzymatic methodologies. Elevated bilirubin levels interfere with the accuracy of diagnostic tests through spectral absorbance, chemical reactions, and matrix effects. These interferences can lead to spurious results, potentially causing misdiagnoses or inappropriate treatment plans.

Effective management of icterus-related interference involves implementing strategies such as blanking methods, the use of bilirubin-neutralizing reagents, and the application of wavelength-specific modifications to minimize spectral distortion. Automated analyzers equipped with bilirubin detection algorithms offer an additional safeguard, enabling laboratories to flag and address affected samples promptly. Finally, reporting test results with annotations regarding potential icterus interference is critical for ensuring clinicians are informed of the limitations in interpretation.

By adopting these mitigation strategies, laboratories can reduce the impact of icterus on assay accuracy, ultimately improving the reliability of laboratory results and supporting better clinical outcomes.

Conclusion

Endogenous interfering substances—hemolysis, lipemia, and icterus—are among the most common causes of pre-analytical and analytical errors in clinical laboratories. Each of these interferences has unique mechanisms that can alter test accuracy, leading to misdiagnoses or inappropriate clinical management.

- Hemolysis disrupts assays through the release of intracellular components, causing spectral interference, chemical reactions, and dilution effects.

- Lipemia introduces turbidity and volume displacement, distorting spectrophotometric and immunoassay-based measurements.

- Icterus affects assays via bilirubin’s strong spectral absorbance and chemical reactivity, impacting a wide range of diagnostic tests.

To ensure accurate and reliable results, laboratories must adopt robust protocols for detecting and mitigating these interferences. Key strategies include proper sample handling, automated interference detection, and the use of alternative analytical methods. Laboratories should also provide clear documentation of potential interference in patient reports to guide clinicians in interpreting results.

By addressing these challenges proactively, clinical laboratories can minimize the impact of hemolysis, lipemia, and icterus, improving the reliability of diagnostic testing and enhancing patient care. Further advancements in technology and assay design will continue to play a pivotal role in mitigating the effects of these endogenous substances, ensuring the highest standards of accuracy in laboratory medicine.

Leave a comment